____________________________________________________________

22 April

A new post on the Cinema Reborn blog page is a must for nostalgics who recall the days of altruistic distribution and exhibition of art house movies including, back in 1971, one of the star attractions of Cinema Reborn 2019 Jacques Rivette’s The Nun/La Religieuse.

You can read the story if you Click on this link

____________________________________________________________________________________________

OPENING NIGHT FOR CINEMA REBORN 2019

OPENING NIGHT FOR CINEMA REBORN 2019

Kim Hunter, David Niven A Matter of Life and Death (Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger, UK, 1946)

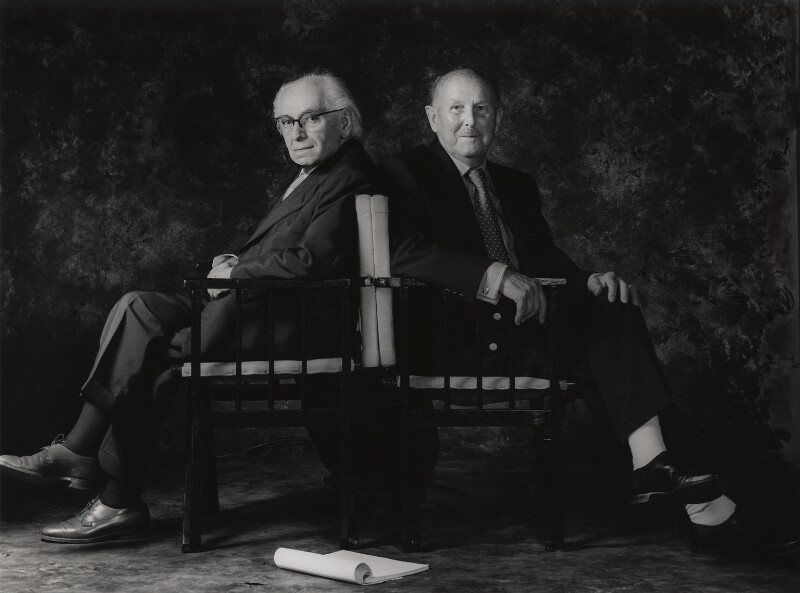

MICHAEL POWELL AND EMERIC PRESSBURGER

The historic director-writer collaboration of these two great artists began in 1939 with The Spy in Black and continued with two more movies set at the beginning of WW2, Contraband (1939) and 49thParallel in 1940. Powell and Pressburger subsequently formalized their creative partnership as “The Archers” with their next picture, One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942) and would continue through the fifties and sixties with another 15 films as the most distinctive writer-director team in British cinema.

Their peak period runs from 1943 to 1952 when they were responsible for some of the very greatest British movies ever made, sharing Pantheon status with only a handful of other UK directors , notably Robert Hamer, and Alexander Mackendrick. They seem today like titans of poetic, imaginative cinema, in stark comparison to the relatively prosaic work of then Academy darlings like David Lean and Carol Reed. Their collaborations temporarily ended in 1960 when Powell made his solo masterpiece, Peeping Tom, but were rekindled in the buoyant sunshine and optimism of 60’s Australia, of all places, where Powell directed, and Emeric wrote – pseudonomously as “Richard Imrie”- They’re a Weird Mob (1966). Their very last work was the short children’s fantasy feature, The Boy who Turned Yellow in 1972.

THE FILM

Powell had made A Canterbury Tale in 1944 at the request of the British Information Ministry which was trying to encourage wartime “fraternization” between locals and the visiting American servicemen, where frictions and rivalries were running hot. The film was contrived to embed the message within a droll mini-adventure seeking the notorious “glue man” who is doing despicable things to girls’ hair on the trains, and a budding romance between a Yank servicemen and an English girl.

Powell had made A Canterbury Tale in 1944 at the request of the British Information Ministry which was trying to encourage wartime “fraternization” between locals and the visiting American servicemen, where frictions and rivalries were running hot. The film was contrived to embed the message within a droll mini-adventure seeking the notorious “glue man” who is doing despicable things to girls’ hair on the trains, and a budding romance between a Yank servicemen and an English girl.

It is instructive to note that Powell had earlier clashed with then PM Churchill in 1943 over a number of scenes to their sublime The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. Churchill insisted on cuts of scenes, some of them read and played by Anton Walbrook as Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff, as too German friendly for a wartime picture. At this point it’s worth noting that Powell has described his own politics as High Tory with a tilt to Labour. It may well have been the dictatorial highhandedness of Churchill which mellowed his tone.

It was from this movie on that the duo wrote and directed a series of incomparable films about Britain and the British, as an Island, the home of mythical, even magical history and a primeval past. No more British a director has ever made a career of such a series of love songs to his patrimony and these Archer films, collaborations of Powell and his friend, the Hungarian “refugee” Emeric are among the greatest in English language cinema. Blimpis my own masterpiece but the following half dozen films are so close as to touch its wings.

By the end of 1945, finally free from war and able to get the big Technicolor camera rigs back from Larry Olivier who had been using them to shoot Henry V, the partners went to work again on an informal suggestion from the Information Ministry to do another picture encouraging fraternization.

The result is A Matter of Life and Death. The movie blends a number of binaries, the first is the apparent survival against the odds of a young airman who dives without parachute from his burning plane to land on the coast, still alive where he is joined by an American girl working at airport control and a local doctor, played by Powell and Pressburger’s most commensurate actor, Roger Livesey. The movie’s narrative falls back and forth between “reality”, “hallucination” and visions including a representation of what might be some sort of afterlife. The present day is filmed in literally gorgeous three strip Technicolor by new Director of Photography Jack Cardiff, on his first feature, and in a stroke of genius “the other side” is filmed in totally desaturated Monochrome. Powell’s politics are mischievously at play here, with the black and white “Heaven” designed by Archers’ Production Designer Alfred Junge as a Deco-Moderne infinite city in the style of W.C. Menzies’ sets for his 1936 movie of H.G.Wells’ Things to Come.

This monochrome paradise feels like a kind of near-flawlessly ticking model for a future civil service Britain, one which indeed was to come into being in one way and another with the beginning of ten years of post-war austerity, the redemptive succession of the great Clement Atlee Socialist government in July 1945, and the creation of the British Welfare State and Aneurin Bevan’s National Health.

Even an avowed Tory like Powell was content to signal, with the presence of Kathleen Byron as the Head Counter Check-in Angel that the place couldn’t be all that bad.

The movie plays with the idea of a death escaped, perhaps not deserved and counters it with a death from a civilian that may answer that contention. Or not. There is a key scene to begin the second act of the film in which every aspect of the filmmakers’ imagination comes to life. Airman Peter Carter has come to meet June and Doctor Frank at a local hall. The sequence begins with the business of an amateur theatrical company enlisting both US Servicemen and local girls and boys who are rehearsing A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Mendelssohn’s incidental music is on the soundtrack. Peter and June sit down, Peter still uneasy from a recent encounter with his Heavenly “visitor”. The score (by house composer for the Archers, Allan Gray) suddenly turns atonal from the Mendelssohn to a solo piano. Powell cuts from the master wide shot of Peter and June to a montage of images in close-up, all dominated by Black and White composition, referring to the non-colors of “heaven”: a piano keyboard which begins pounding Gray’s four-four “announcement” score, then a black and white chessboard, then he cuts back to the wide shot with its full colour. Frank asks Peter about his headaches and visions and asks him (and us) to carefully gaze at the back of the hall (and the image).

There, in layers of decor are keynotes of burning red, and orange, the same colours that signalled the impending fiery death of the burning plane at the movie’s beginning.

THE RESTORATION

This new digital restoration, supervised by Grover Crisp, was created in 4K resolution at Sony Pictures Entertainment. The original 35mm three-strip Technicolor negatives were scanned at Cineric in New York on the facility’s proprietary 4K high-dynamic-range wet-gate film scanner. An earlier photochemical restoration — by Sony Pictures Entertainment, the British Film Institute, and the Academy Film Archive, with the participation of Jack Cardiff — was used as a colour reference. The original monaural soundtrack was remastered from a 35mm nitrate variable-density optical soundtrack print at Deluxe Audio Services in Hollywood, using the iZotope mastering suite in addition to Capstan for music wow.

CREDITS

Dirs, Prod, Scr: Michael POWELL , Emeric PRESSBURGER | UK | 1946 | 94 mins | B&W, Colour | Sound | Eng. | DCP (originally 35mm) | PG.

Prod Co: The Archers | Photo: Jack CARDIFF | Edit: Reginald MILLS | Des/Art: Alfred JUNGE | Costumes: Hein HECKROTH | Sound: C.C. STEVENS | Music: Allen GRAY. Source: Park Circus.

Cast: David NIVEN (Peter D. Carter), Kim HUNTER (June), Roger Livesey (Dr. Frank Reeves), Marius GORING (Conductor 71), Robert COOTE (Bob Trubshaw), Kathleen BYRON (Angel), Abraham SOFAER (The Judge), Raymond MASSEY (Abraham Farlan).

Source: Park Circus

Notes by David Hare